Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) chemicals from household and commercial products may find their way into water, soil, and biosolids. As a result, PFAS have been found in people, fish, and wildlife all over the world.

The PFAS Road Map (Updated 2023) has helped state officials to identify sources and reduce the use, release, and public exposure of PFAS in Vermont.

Below you can find information about testing for PFAS in public and private drinking water sources. ⬇️

Private Water Supplies

Approximately 40% of Vermonters get their drinking water from a private residential well or spring. If you do not receive a water bill or pay for water another way, you are likely on a private well or spring.

In Vermont, there is no requirement to test for PFAS in a private well or spring. The best way to know if you are being exposed to PFAS in your drinking water is to test. Residential well or spring users can obtain water sample bottles by contacting an accredited laboratory on this list.

Given the prevalence of PFAS in many products, including clothing, and the ability of lab equipment to quantify low levels, care must be taken when collecting samples.

The Department of Environmental Conservation continues to investigate sources of PFAS contamination that may be impacting private wells and evaluate which homes need to be sampled in areas where residents are using private drinking water wells that could be impacted from a nearby PFAS source. If you think your well may be impacted by a PFAS source, please contact the Waste Management and Prevention Division at (802) 828-1138.

Unless you obtain your water from a public water system, your water may contain other contaminants such as arsenic, uranium, radon, manganese, nitrate and bacteria that present health risks and that are naturally occurring or originate from nearby land uses. The Vermont Department of Health recommends you test your well or spring on a regular basis to make sure your water is safe to drink. More information regarding recommendations for testing private wells can be found at: Residential Drinking Water Testing.

If you have questions about your water quality sampling results or treatment options please contact the Private Drinking Water Program at the Vermont Department of Health at 802-863-7220 or 800-439-8550.

Public Drinking Water Systems

Approximately 60% of Vermonters receive drinking water from a public drinking water system. If you receive a water bill or have related expenses as part of association fees or dues, your drinking water likely comes from a public water supply. While many public drinking water systems are run by towns or municipalities, some systems are operated by homeowner associations, manufactured housing communities, and other similar entities with their own source(s) of water.

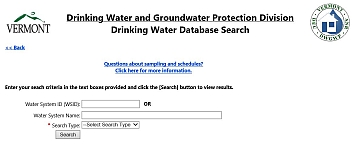

All Non-Transient Non-Community and Community Water Systems are required to sample for PFAS at a frequency based on their sample results. The link below provides the PFAS sample results for Vermont’s public drinking water systems. Many water systems have sampled for PFAS three times, depending on the results, some systems have sampled much more. If you have questions about the data or having trouble locating data for a specific public drinking water system, please contact the Drinking Water and Groundwater Protection Division at (802) 828-1535.

➡️ PFAS Test Results from Public Drinking Water Systems

Rulemaking: PFAS Contaminant Level

The Vermont Water Supply Rule contains a Vermont-specific Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) and routine monitoring frequencies for PFAS at public drinking water systems. The MCL is 20 nanograms per liter (ng/L) and it is for five PFAS in drinking water: PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid), PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonic acid), PFHxS (perfluorohexane sulfonic acid), PFHpA (perfluoroheptanoic acid), PFNA (perfluorononanoic acid). The sum of these five PFAS cannot exceed 20 ng/L.

If PFAS are found above the MCL, water systems will be required to protect public health through public notice, and develop both a short-term and a long term plan to address PFAS contamination.