Vermont contains a great diversity of wetlands, ranging from open water habitats to rich forested swamps. Wetlands vary because of differences in hydrology, parent soil material, historical land use, topography and other factors. These differences make each wetland unique in its appearance, biota, and function in the landscape. Some general wetland types present in Vermont include open water wetlands, emergent wetlands, scrub-shrub wetlands, forested wetlands, wet meadows, peatlands, and vernal pools.

Forested Swamps

Swamps are wetlands that are dominated by woody vegetation – either trees or shrubs. Many woody plants are adapted to tolerate wet conditions; however, they are less able to tolerate prolonged or frequent flooding than their herbaceous counterparts. Swamps develop in settings where the soil is saturated or flooded for long enough during the growing season to favor wetland plants, but where the water level is low enough – or recedes for long enough -- to allow woody plants to germinate, grow to maturity, and reproduce.

Swamps are wetlands that are dominated by woody vegetation – either trees or shrubs. Many woody plants are adapted to tolerate wet conditions; however, they are less able to tolerate prolonged or frequent flooding than their herbaceous counterparts. Swamps develop in settings where the soil is saturated or flooded for long enough during the growing season to favor wetland plants, but where the water level is low enough – or recedes for long enough -- to allow woody plants to germinate, grow to maturity, and reproduce.

Forested swamps occur in seasonally flooded areas along lakes and rivers, and in isolated depressions. They may be dominated by hardwood or softwood trees. Hardwood swamps are common in comparatively warm, low-elevation areas of the state, while softwood swamps are more common in colder areas such as the Green Mountains and the Northeast Kingdom. Some trees are more tolerant of flooding than others, and species composition of forested swamps is heavily influenced by hydrology. Common hardwood species include red maple, green and black ash, silver maple, American elm, and swamp white oak, and common softwood species include eastern hemlock, northern white cedar, black spruce, balsam fir and tamarack. During the growing season, a lush layer of ferns, mosses, and/or sedges is often present on the forest floor.

Shrub Swamps

Shrubs are relatively short woody plants that have multiple stems and branches. Wetlands dominated by shrubs are extremely variable; some are early-successional precursors to forested swamps, while others are mature natural communities in their own right. Shrub species such as alders, willows and dogwoods are more tolerant of flooding than most trees, and can grow and reproduce more quickly. Shrub swamps occur where flooding is too frequent or prolonged to support trees, or in areas impacted by other disturbances. Former agricultural lands and abandoned beaver ponds tend to develop into shrub swamps, and if left undisturbed, these may become forests. Shrub swamps also occur along small rivers and streams, where flooding occurs repeatedly during the growing season. Certain shrub species, such as sweet gale and buttonbush, are extremely tolerant of wet conditions. Swamps dominated by these species may never become forested and persist for centuries.

Shrubs are relatively short woody plants that have multiple stems and branches. Wetlands dominated by shrubs are extremely variable; some are early-successional precursors to forested swamps, while others are mature natural communities in their own right. Shrub species such as alders, willows and dogwoods are more tolerant of flooding than most trees, and can grow and reproduce more quickly. Shrub swamps occur where flooding is too frequent or prolonged to support trees, or in areas impacted by other disturbances. Former agricultural lands and abandoned beaver ponds tend to develop into shrub swamps, and if left undisturbed, these may become forests. Shrub swamps also occur along small rivers and streams, where flooding occurs repeatedly during the growing season. Certain shrub species, such as sweet gale and buttonbush, are extremely tolerant of wet conditions. Swamps dominated by these species may never become forested and persist for centuries.

Floodplain Forests

Floodplain forests are unique, seasonally flooded communities that occur along our larger rivers and lakes. The wide, fairly level terrain of these forests provides a temporary storage place for floodwaters. The water dissipates energy as it spreads across the floodplain landscape, losing power and preventing damage downstream. The roots of large, flood-tolerant trees like silver maples and elms stabilize the soil, reducing erosion along the banks. Sediments carried by the rushing waters are deposited within the forest, providing the rich floodplain soil (alluvium) that has been valued by farmers for millennia. The annual spring flooding leaves the forest like a wasteland covered in bare soil and woody debris, but in early summer, the forest floor transforms into a lush green carpet of ferns and other plants.

Floodplain forests are unique, seasonally flooded communities that occur along our larger rivers and lakes. The wide, fairly level terrain of these forests provides a temporary storage place for floodwaters. The water dissipates energy as it spreads across the floodplain landscape, losing power and preventing damage downstream. The roots of large, flood-tolerant trees like silver maples and elms stabilize the soil, reducing erosion along the banks. Sediments carried by the rushing waters are deposited within the forest, providing the rich floodplain soil (alluvium) that has been valued by farmers for millennia. The annual spring flooding leaves the forest like a wasteland covered in bare soil and woody debris, but in early summer, the forest floor transforms into a lush green carpet of ferns and other plants.

Prior to the arrival of the European settlers in the late 18th century, vast expanses of floodplain forest probably occurred along all of Vermont’s major waterways. Most of Vermont’s floodplain forests have since been converted to agricultural use, and intact examples of this wetland type are now uncommon. In addition to continued agricultural use, invasive plants and dams pose significant threats to these forests. With the soil left exposed after flooding, fast-growing and quickly-spreading invasive plants easily colonize the forest floor, and out-compete native plants such as ostrich and sensitive ferns. Dams modify the natural flooding regime, and trap sediments that would otherwise be deposited as alluvium. The significant functions and values provided by this wetland type make the remaining fragments a high priority for protection.

Marshes

Marshes are characterized by standing water and emergent vegetation such as cattails, bulrushes, sedges, and wild rice. They occur along lake and pond margins, in beaver meadows, in floodplain backwaters, and in isolated basins. The plants that grow in marshes vary depending on the depth of water and the duration of flooding; some are only flooded seasonally, while others have permanent standing water up to six feet deep. Marshes are often interspersed with other wetland types such as shrub swamps. They exist in areas where the water is deep enough for a long enough period of the growing season to prevent establishment of trees and shrubs.

Marshes provide important habitat for many wildlife species including beavers, muskrats, waterfowl, turtles, frogs, and various songbirds. As the gateway between upland areas and open water, these wetlands are essential for protecting water quality; marsh plants capture sediments and filter out pollutants and excess nutrients before they enter lakes, ponds, and rivers. Marshes also provide immense aesthetic value, as well as opportunities for hunting, birding, paddling, and other recreational activities.

Bogs

Bogs are mystical environments, with their famously preserved “bog bodies,” spongy ground surface, dwarfed trees, and strange, carnivorous plants. They form in depressions with poor drainage, where precipitation is the only source of water and nutrients. Bogs in Vermont are dominated by Sphagnum moss, which is specially adapted to waterlogged, nutrient-poor conditions. The cool environment, scarce minerals and nutrients, and high acidity slow the process of decomposition, and dead vegetation accumulates in a thick layer of poorly decomposed material called “peat.” Bogs form when a mat of peat begins to form along the margins of a flooded depression, and gradually closes in toward the center. In many bogs, a central area of open water is encircled by a floating peat mat, dominated by low-growing herbaceous vegetation, and dotted with small trees. Other bogs are more densely forested, primarily with black spruce and tamarack. The depth of peat in a bog can be many meters deep.

True bogs are ombrotrophic – that is, they have no inflow or outflow of water and nutrients, and only receive inputs from precipitation. Most of the wetlands referred to as bogs in Vermont are actually fens, which are also peatlands but are minerotrophic, meaning they receive mineral inputs from groundwater. Learn more about fens below.

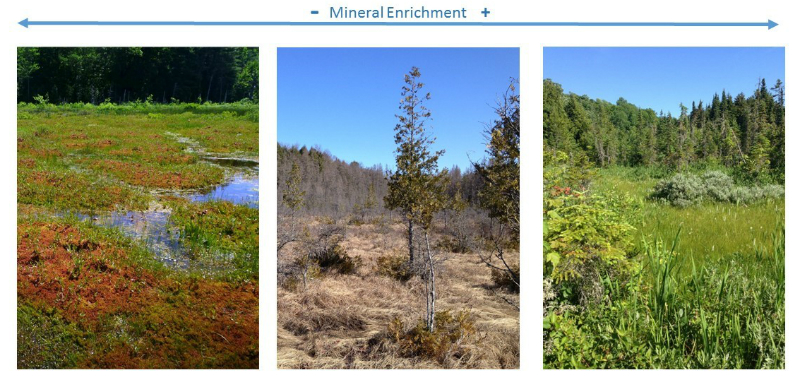

Fens

Like bogs, fens are peatlands where slow decomposition causes dead vegetation to build up in a thick, floating mat. Unlike bogs, however, fens receive mineral inputs from groundwater in addition to precipitation (the technical term for this characteristic is minerotrophic). The level of mineral enrichment in a fen depends on the chemistry of the bedrock through which the groundwater flows. Fens with low levels of enrichment are similar to bogs, with plant species specially adapted to poor conditions, such as Sphagnum moss and pitcher plants. These communities, aptly named “poor fens,” are characterized by thick hummocks of Sphagnum and other bog plants interspersed with enriched hollows of sedges and other non-bog plants. As enrichment increases, biological processes such as decomposition can occur more rapidly, and the thickness of the peat mat decreases. Nutrients are more readily available, and plants without special adaptations for bog-like conditions are able to survive. Fens with the highest levels of enrichment are plant diversity hotspots. These “rich fens” are home to a wide variety of non-sphagnum mosses, sedges, and other herbaceous vegetation. Rich fens only develop under very specific conditions, where groundwater seeps into a wetland through calcium-rich bedrock. They are quite rare, both in Vermont and on a global scale. “Intermediate fens” fall between rich and poor fens in their levels of enrichment, and in Vermont, they tend to be dominated by a particular species of plant called hairy-fruited sedge (Carex lasiocarpa).

Seeps

Seeps occur in areas where bedrock impedes the downward flow of groundwater, causing it to discharge at the surface. These are generally small wetlands surrounded by upland habitat, which tend to be located along the base of slopes or terraces. Pockets of a forest where bright green sedges and mosses emerge from spongy wet soil and leaf litter can be easily identified as seeps. With a constant supply of groundwater, these important wetlands often serve as the headwaters to streams that flow into larger rivers.

Groundwater generally remains at a constant temperature throughout the year (about 47°F in Vermont). Because the water temperature remains above freezing, new plants emerge from seeps in early spring, when the rest of the landscape is frozen and food is scarce. This special feature makes seeps important for black bears, deer, turkey and other animals recovering from winter stress. Even in the depths of winter, the warm groundwater melts the snow and exposes seeds, plants, and invertebrates for foraging animals. Both humans and wildlife use seeps as a year-round supply of spring water. These wetlands are also important breeding grounds for amphibians.

Vernal Pools

Vernal pools occur in small topographic depressions with poor drainage, where runoff from melting snow and rain collects in spring. The pools are only flooded temporarily; they dry up completely by early to mid-summer, and may flood again with heavy fall rains. Vernal pools are not typically connected with streams or other wetlands or water bodies – they are isolated wet areas within upland forests. Because they are small and are only flooded for a short period of time during each year, vernal pools are often overlooked. While most wetlands can be identified by characteristic vegetation, plant growth in vernal pools is sparse. Instead, vernal pools must be identified based on their characteristic animal inhabitants.

Vernal pools provide critical breeding habitat for many amphibians. Spring peepers, spotted salamanders, wood frogs and others migrate from surrounding forests to lay their eggs in the pools in early spring, and their young reach maturity and disperse before the water evaporates. Many invertebrates also live in vernal pools, including a tiny crustacean called the fairy shrimp. The animals in vernal pools avoid predation by fish, which require permanent standing water to survive; however, they still serve as food for birds and other wildlife. Because amphibians must migrate from surrounding uplands, the landscape surrounding a vernal pool is just as important as the pool itself.

Wet Meadows

This wetland type includes many abandoned agricultural fields and formerly flooded beaver ponds, wet portions of hayfields, as well as other seasonally flooded or saturated areas where non-woody plants are dominant. Wet meadows occur in a wide variety of settings, and the vegetation varies considerably. In general, the dominant plants are grasses and sedges, mixed with various wildflowers and occasional shrubs. Standing water is not always present in wet meadows, and they are often overlooked. In actively mowed fields, they can be difficult to identify. Wet meadows are often associated with larger wetland complexes that may include shrub swamps, forested swamps, and marshes. If left undisturbed, wet meadows may succeed to shrub or forested wetlands over a period of decades.

These unassuming wetlands play an important role in water quality protection, because the dense vegetation binds and stabilizes the soil, and many are connected to tributary streams. They also provide habitat for many amphibians, birds, small mammals and invertebrates.

Links of Interest

- Wetland, Woodland, Wildland: A Guide to the Natural Communities of Vermont. A great place to learn more about the different types of wetlands in Vermont. Written by E.H. Thompson and E.R. Sorenson. 2000 and 2005. Published by The Nature Conservancy and Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife, distributed by University Press of New England.